‘Haunted’ by the Crowe murder case, defense attorney proposes Children’s Bill of Rights

Many seasoned lawyers have a case or two that they never forget. For Donald McInnis, a longtime criminal defense attorney in San Diego, it was the 1998 murder of Stephanie Crowe.

“It haunted me for years,” he said. “It still haunts me.”

Officially, the knife that kills the 12-year-old Escondido girl in her bedroom remains unsolved. But that’s not what bothers 76-year-old McInnis the most.

He is haunted by the realization that his client, one of three teenagers originally charged in the case and later released, could easily be convicted and imprisoned, perhaps for life.

“People who think this can’t happen to their children need to think again,” said McInnis.

Last month he published a new edition of his 2019 book on The She Is So Cold case, which contains recommendations on how to improve the justice system. He hopes to rule out the mistakes that plagued the Crowe case and drown them in reasonable doubt so that justice is unlikely to ever be achieved.

He proposes a child rights ordinance which, among other things, requires the presence of a parent or legal guardian when a minor is questioned by the police. He wants the Miranda Alert officers to give the suspects: “You have the right to remain silent,” etc. – supplemented with language a child can understand.

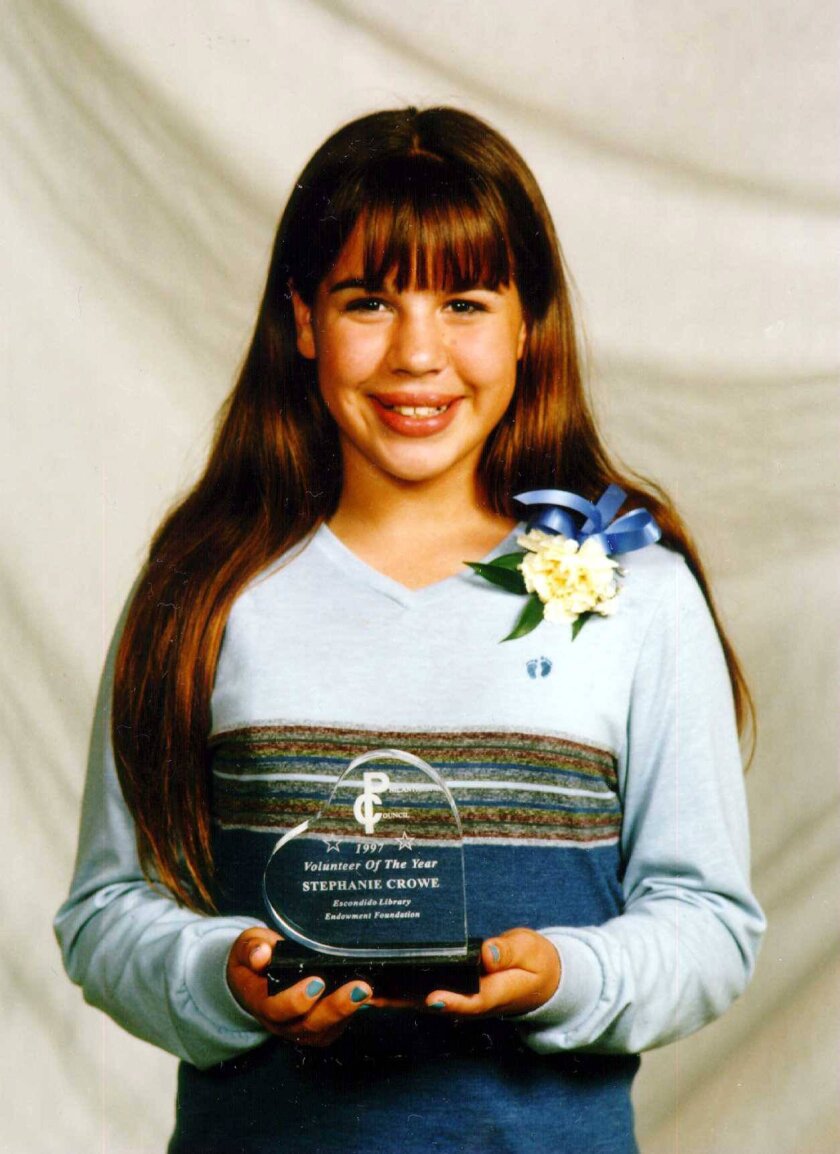

Stephanie Crowe.

(Handout photo)

“Studies have shown that minors – children and adolescents – are unable to fully understand the meaning of rights,” writes McInnis. “Therefore, minors cannot” knowingly and intelligently waive their constitutional rights “prior to interrogation, as required by law.”

It is an issue that is attracting attention in other cities amid a nationwide conversation about police reform. Triggered by the murder of George Floyd in police custody in Minneapolis last year, the main focus of the discussion was on curbing alleged physical abuse. But psychological and emotional compulsion are also carefully examined.

In the Bronx, New York, prosecutors are reviewing 31 murder convictions based on confessions from three detectives who worked together in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In one of their cases, a 16-year-old boy falsely confessed to killing his mother and spent 20 years in prison before being exonerated.

Nationwide, studies have shown that false confessions, often obtained through high pressure interrogation techniques, are a leading cause of unlawful convictions in the United States. The National Registry of Exonerations lists them as responsible for 12 percent of the 2,750 cases documented since 1989.

The Crowe case, McInnis said, could have been one of them.

An inside job?

In the early hours of the morning after Stephanie Crowe was stabbed nine times, Escondido police concluded it was an inside job and focused on her 14-year-old brother Michael.

Detectives interrogated him for about eight hours for two days without his parents’ consent or knowledge. They lied – a tactic that is legal – and told him they found blood in his bedroom. They promised him forbearance if he got clean and indicated the horrors that awaited him if he were taken to adult prison. They said his parents believed he was guilty and never wanted to see him again, another lie.

Michael eventually confessed to the murder and emulated the detectives’ suggestions that his personality had two sides and that the “bad Michael” had taken power in a rage fueled by sibling rivalries.

Detectives also picked up Michael’s best friend Joshua Treadway, 15, and interrogated him for about 18 hours for two days. They also lied to him about evidence, saying he was being used in the fall by Michael Crowe. Treadway confessed, saying he acted as a lookout while Michael and a third teenager, Aaron Houser, snuck into Stephanie’s room.

15-year-old Houser was also interviewed, and although he denied any involvement in the murder, he gave a hypothetical “chilling” description of how he might have committed it.

The three teenagers were arrested and charged with murder as adults. In a pre-trial hearing, a Supreme Court judge threw back Michael’s confession, Houser’s testimony, and most of Treadway’s confession, ruling that they had been illegally coerced or had not been given the necessary Miranda warnings.

A two-hour part of Treadway’s confession, in which the alleged murder conspiracy was described in detail, remained permissible. The prosecutors decided to try him first. During the jury’s selection, DNA tests found Stephanie’s blood on an item of clothing – not something that belonged to the teenagers, but on a sweatshirt worn by a homeless man wandering around the Crowe neighborhood on the night of the murder knocked and peered in windows looking for a woman he knew.

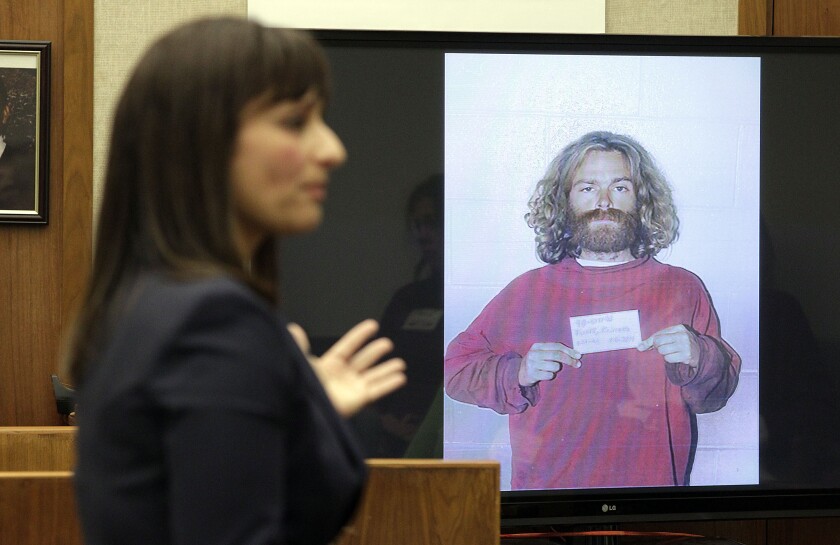

Opening arguments in the retrial of Richard Tuite in 2013 for the murder of Stephanie Crowe.

(John Gastaldo / John Gastaldo / UT San Diego)

The case against the young people was dropped and the homeless man Richard Tuite (28) was brought to justice. He was convicted of voluntary manslaughter in 2004 and sentenced to 17 years in prison. A federal appeals court overturned the verdict, ruling that Tuute’s attorney had been wrongly curtailed while cross-examining a prosecutor’s witness. Tried again in 2013, Tuite was acquitted.

By then, Michael Crowe and Treadway had sought and received a rare determination of actual innocence from a judge who ruled that “there is no reasonable reason” to believe they were involved in the murder. Houser was not part of the motion, but the result applies to him, according to the attorneys involved.

The Crowe family sued for various civil rights violations and received more than $ 9 million worth of settlements, most of them from the cities of Escondido and Oceanside, which employed the detectives interrogating the youth.

The youthful brain

McInnis represented Houser in the case after he was approached by a family friend. He had worked in criminal matters earlier in his career, both as a prosecutor and as a public defense attorney, but was in private practice at the time, primarily concerned with personal injury, insurance, and other civil matters.

He said he knew immediately that if they made it in front of a jury, the confessions would be a problem, even to a limited extent.

“It’s so damned when a suspect says I did it, which is why the police work so hard to get a confession,” McInnis said. “It is the strongest evidence any prosecutor can produce.”

He said he was preparing his Houser defense to include experts who would explain why minors like Treadway lack the mental faculties and life experience to understand what happens during an interrogation. Why they are so willing to obey and please those in authority. And why they falsely confess.

These are topics he explores further in scientific articles, including one that will be published shortly in the Dartmouth Law Journal and co-authored with a neurologist.

McInnis said he decided to write the book after meeting a group of people at a senior citizen facility about 12 years ago, long after the teenagers were freed from the murder and received widespread media coverage.

“They all thought the boys did it,” he said. “I remember a man who said to me, ‘The cops would not have arrested you and the prosecutor would not have prosecuted you if you were not guilty.’ That was a shock to me. “

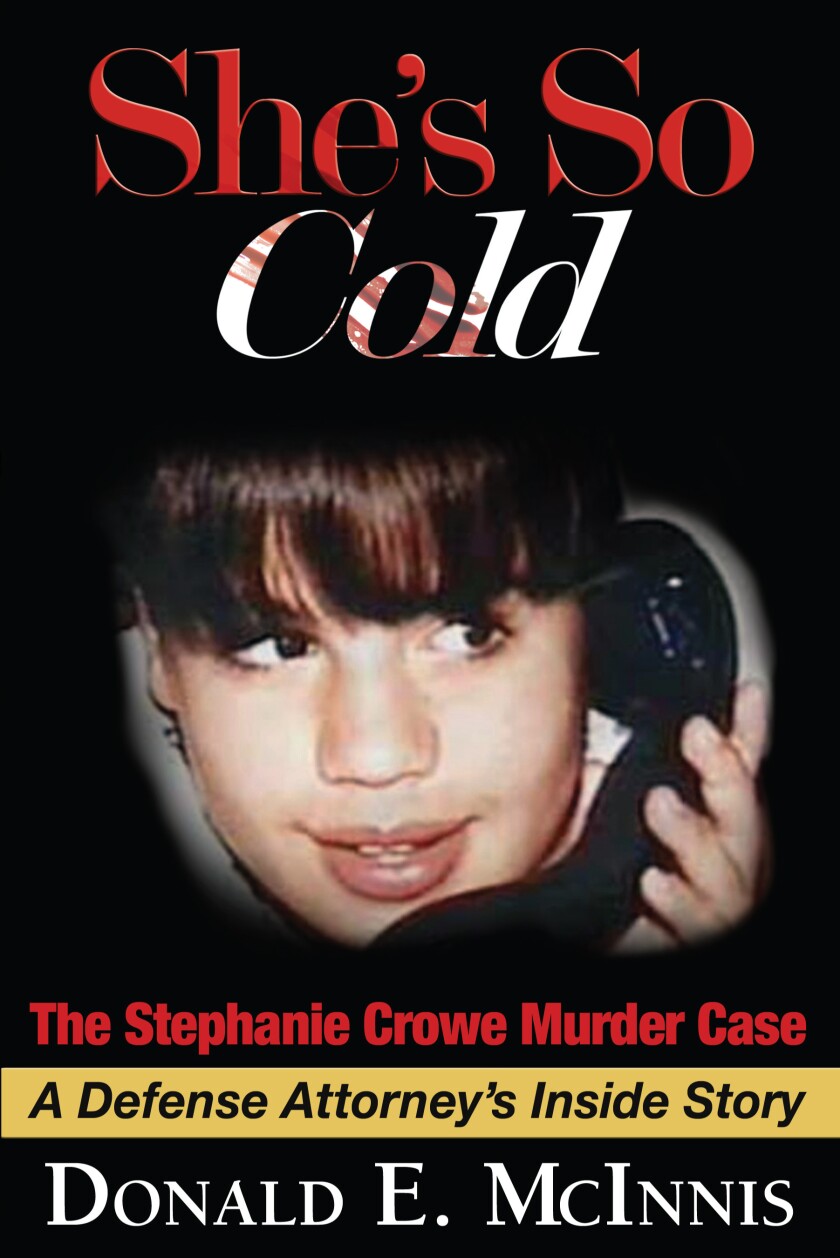

Cover of a new book on the Stephanie Crowe murder.

(Courtesy photo)

The book takes an in-depth look at the interrogations of teenagers that have been videotaped and describes the training and techniques detectives routinely use to obtain confessions.

McInnis said he wanted to create a record so people can better understand what happened in one of San Diego County’s most heartbreaking judicial failures. The book’s title, “She’s So Cold,” comes from a quote from Stephanie Crowe’s mother Cheryl, who shouted it out loud as she cradled her daughter’s body shortly after the girl was found on the bedroom floor.

But he also wants the book to serve as a warning. California law has made some changes to protect minors during police interrogations, he said, but problems remain. The basic query methods are the same.

“While (Michael Crowe, Treadway and Houser) can never escape the pictures of what happened to them, I believe that we as a society must not close the book on this unfortunate incident,” he writes. “We must always remember that these children could have been our own.”

Comments are closed.